In the stillness of a winter morning, I cast my hearing to the brittle dawn.

The night was silver and dusted

in diamonds.

The frost twinkled

like the light of a thousand

miracles come true.

In the stillness of a winter dawn, the sound of Life is frozen

silent.

It screams in the roaring rustle of stationary leaves and

rumbles in the crunch of snow beneath your feet.Which are numb.

If I stand still I hear my heart beat.

The sun whispers salmon on the crisp white mountains.

I hear my heartbeat. I search for fire.

I walk into the woods.

A solitary soldier exhausted from the savage stillness.

The sun rises over the Seven Sisters in Carcross, Yukon Territory. (December, 2017) It’s been referred to as a place where people go when they want to be alone.

NORTH

It’s the kind of cold that’s written about in the most tragic of literature. Yet, none of those high-brow, artistic strings of words do this scathing temperature any justice. Minus 30 degrees centigrade is almost unimaginable for those of us who live in more temperate climes.

Indescribable.

And that’s not even counting the wind chill.

You can put on the thickest of down jackets, the most formidable of thermal footwear, and that will still fail to make you feel remotely human.

The lowest temperature recorded in the Yukon is -63 degrees celsius in 1947, the coldest ever in North America. At that level, it’s difficult to breathe in the scalding air, spit freezes before hitting the ground, wood is like rock, metal snaps, and sound – as in any temperature below freezing – is heightened because of denser air and the strong surface temperature inversion. (Source: Yukon News, and The Weather Doctor.)

It’s the kind of cold that separates you from your body by the mere fact that it leaves you incapable of feeling anything corporeal.

Not your feet.

Not your hands.

Not even your face.

Everything is numb.

And somehow, right here, right now — that is exactly how I need to feel.

Waiting for miracles. Whitehorse, Yukon Territory, Canada. (Photo by: K. Visconti)

NO GUARANTEES

Every year, hundreds of thousands of tourists visit the north of Canada in the hopes of seeing one of nature’s most beautiful wonders — the Aurora Borealis. The Northern Lights.

They’ve been called “nature’s fireworks” and are caused by electrically charged particles from the sun colliding with gasses from Earth as they enter the atmosphere.

The phenomenon creates a dazzling celestial billboard of brilliant neon.

A vivid palette of luminous dancing stardust.

From vibrant green to glowing red and burnished purple.

A magical display.

Green is the most common of Aurora colours, caused by charged particles colliding with oxygen. Red, which is rarer, is produced by higher-altitude oxygen. Purple. or blue, is produced by nitrogen. (Source: Aurora Service.)

That’s if you see it.

Auroras aren’t always visible. The sky may be too cloudy. The moon may be too bright. Or there might be too much light pollution.

Science can now tell us when solar winds might be carrying potential Aurora particles our way, but this doesn’t assure that we’ll actually see them paint the sky.

As it is, such occurrences only happen around the North and South Poles, where conditions are more ‘favourable’ because the Earth’s magnetic field is weakest.

They’re also the coldest places on the planet.

“LUCKY”

Thirty-something Harmony was born and raised in the Yukon. She counts herself lucky to have grown up around the Aurora.

“Not to say we saw it all the time, or sat around waiting for it,” Harmony explained, “but we knew it was there, and all we had to do was look.” She smiled. warmly. “Which we often did.”

No matter how many times she’s seen the lights, Harmony said they still impress.

“It makes you feel — small,” she shared, dreamily. “Reminds you there is so much more to the world.”

It was easy to see that the memory of the lights alone already conjured up feelings of awe.

“There are so many magical things around us.”

Less than 40,000 people live in the Yukon, a territory in northwestern Canada that’s as large as Spain.

“I’ve been here happily all my life,” Harmony stated, half-shocked at the question she was asked, “why would I ever want to leave?”

It’s a sentiment echoed by everyone we met.

LIVING INTENTIONALLY

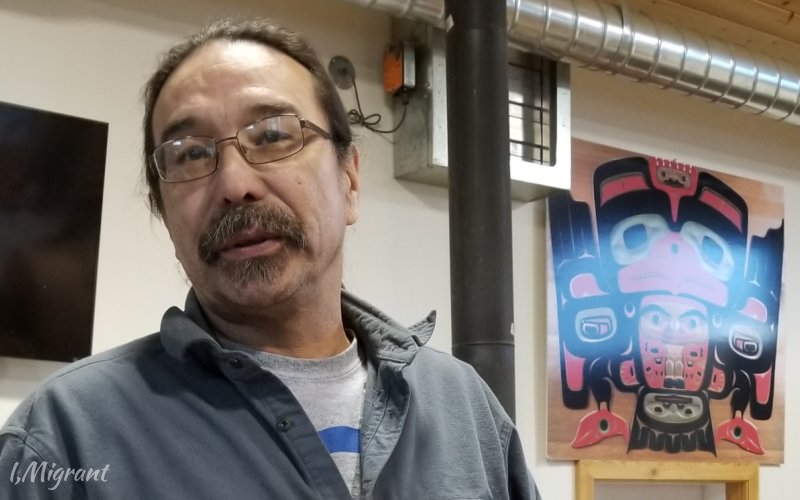

Renowned First Nations woodcarver Keith Wolfe Smarch, also known as Shakoon, which means “Mountain Bird” in his native Tlingit, has work that hangs in British Royal homes.

Fifty-six-year-old woodcarver Keith Wolfe Smarch moved away for work for a few years, but nothing pleased him more than returning to his Yukon hometown.

“Look at this place,” he exclaimed with pride, “it’s beautiful.”

The winter afternoon streamed softly through the glass panes above his studio. It encased everything in an ethereal glow.

Keith’s studio in Carcross, with a view of the mountains.

“The colours, the light…,” Keith started, “clean water, fresh air… I can even eat the fish from the river that’s right at my doorstep!”

Keith is part of the Killer Whale clan of the Tlingit Nation. They’re among the people called First Nations, who are native to the area.

Carcross is one of the Yukon’s southernmost towns. It used to be called Caribou Crossing because of the large herds that crossed here between two lakes during their annual migration. It also became a stopping point for travellers coming from as far south as California who were heading to gold fields further north. (Source: Explore North.)

FIRST RUSH

In the 1890s, an indigenous miner discovered gold which led to a deluge of prospectors from California and Alaska. It changed the Yukon’s course.

“Part and parcel of migration,” Keith said, matter-of-factly. His clan had also moved around until it found a place to settle.

“People will go where there is opportunity,” he added.

And that paves the way for growth.

Boom-towns and settlements sprung up, but the area’s remoteness and arctic climate limited the exploitation of resources.

So, over a century after the Gold Rush, the Yukon remains largely unspoiled and without a highly-developed modern city.

For many people, that is precisely its charm.

Most of the people in the Yukon live in Whitehorse, the capital. Ten percent are migrants. The largest foreign-born population across Canada’s arctic North is Filipino. (Source: Statistics Canada.)

COLD FRONTIER

More than a third of the people now living in the Yukon weren’t born here; they’re here by choice. From as far away as North Africa and Southeast Asia.

For all sorts of reasons.

A love of the outdoors. Adventure. Escape. The quiet. The stillness. The opportunity to engage not just with nature, but with others who feel the same way about the art of living.

It’s a community of kindred spirits.

Germans, Japanese, Indians, even Filipinos who had never experienced snow before.

This is downtown Whitehorse, where you can find restaurants serving a cross-section of cuisine – from Italian to Mexican, to Filipino and Carribean.

Philippine-born ‘Allan’ moved to the Yukon 8 years ago. He works at the aiport.

We first spotted him hugging passengers as they went through for boarding. They treated him like an old friend.

“See you again next season!” he called out as the last group walked away.

Like many others, Allan said it was work that brought him here, but that’s not the only reason he stays.

Government is the major source of economic activity in Whitehorse. The Public Administration sector accounts for 31% of employment. And the average population age is 37. (Source: Yukon Government)

WHERE THE HEART IS

For woodcarver Keith Wolfe Smarch, it’s simple.

“This is me living the dream,” Keith shared, with a gleam in his eyes.

“I enjoy what I do, and I get paid for it.” He chuckled warmly.

Keith walked us all around his studio and thoughtfully explained every tool he used in his craft.

He stopped at the large cedar trunk in the middle of the room.

“It’s about finding – and following – one’s passion.”

Totems are an important part of Tlingit culture. They’re sacred objects and spirit guides that serve as emblems of a family, or tribe. A totem pole is a vertical arrangement of several totems that tell a story.

“Love is stronger than tradition.” – Keith Wolfe Scmarch, Tlingit artist

It was a profound glimpse into his world.

“Sure I’ve made mistakes, still do,” Keith stated, as he put blade to wood, “but now, I call them ‘changes‘.”

Or indeed, challenges.

Another warm hearty laugh.

“You adjust,” Keith offered, triumphantly, “everything evolves. Like life itself.”

The old railway in Carcross. It once made transport easier and connected the town to the gold fields further north.

POTLATCH

It’s the spirit with which the people of Canada’s First Nations survived colonisation and the influx of outsiders. By adjusting.

They adapted, and where they could, they blended the new with traditional ways.

It brought on a new reality of co-existence.

Among the First Nations, there’s even a group called Métis which developed from descendants of mixed-race unions between members of indigenous clans and colonising Europeans.

And what happened to the indigenous miner who first found gold? He made his fortune and donated his land for a railway – on the promise that his people be given jobs.

It’s the First Nations custom. To give away possessions for the greater good.

It’s a part of their culture that remains to this day.

In ceremonies called potlatch, First Nations people still exchange gifts to redistribute wealth. Doing so reinforces a strong sense of communal responsiblity and elevates the social status of the host.

It’s about stewardship rather than ownership.

By the Yukon river, in Whitehorse. The Yukon economy has long been dependent on mining, but tourism has become a vital component, contributing almost $100 CAD to the territory’s GDP. Almost half a million people visited in 2017. (Source: Canadian Government.)

PROSPECTORS

As much as this place has evolved, there is indeed a part of it that stays constant.

The sense of shared journey. Where no one feels like an outsider – regardless of where they’ve come from.

There is a respect for nature. A respect for silence.

It’s a place where life moves more slowly. Where you stop for hitchhikers, and know the neighbours by name.

Where people find a way to help you when you need it.

Here, everyone is a prospector searching for gold. And if you find it – even the smallest trace – you carry it with you forever.

So, did we see the Northern Lights?

A glimmer of Aurora light on the bank of a frozen lake. (Photo: K.Visconti.)

Yes, a sliver. A slice of glistening green.

It wasn’t the full arc of glowing kaleidoscope colours we had hoped for, but it was enough to shower us in awe.

We’d sat, for hours, around a woodfire stove in a hut by a frozen lake in below freezing temperatures. Sipping Yukon coffee and trading stories with people from all over the world on a similar adventure.

Gathering around the stove for heat in the wall tent.

Every few minutes or so, we’d go outside to peer at the sky.

As Harmony told us, “the anticipation itself is an experience.” She was right.

At around one o’clock in the morning, our gamble paid off.

Aurora Borealis, Yukon. Dec. 26, 2017. (Photo: K. Visconti.)

STRIKING GOLD

In the Yukon, I learned to appreciate that it is in such disembodying cold and stillness that you can see the wonder of life.

It is in such frozen silence that you can hear.

It is in seeming barren darkness that you find the gold.

In the stillness of a brittle morning,

I hear my heartbeat.I find my fire.

I walk into the woods.

A solitary soul

expectantin the splendid silence.

Comments

You’re the best storyteller!

So glad you’ve read it, Doc! Thank you.

Marga

Thanks for sharing. The writing evokes the peace and wonder of the place so well.